The clone wars

Cloning isn’t science fiction anymore.

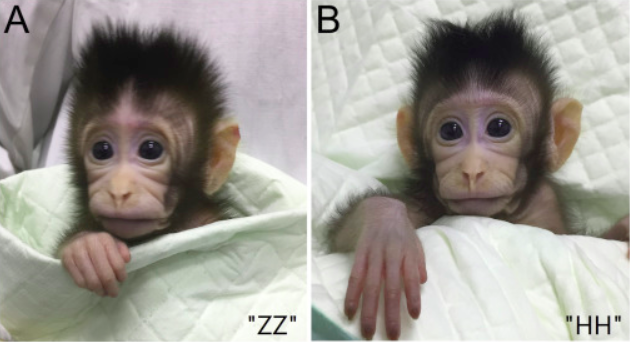

What was once merely fantasy is now a reality: scientists, for some time now, have been cloning animals and refining the process each time. On Jan. 24, National Geographic reported that Chinese researchers used a cutting edge method to successfully clone two macaque monkeys, a first for the scientific community (the last successful cloning was done in 1996 in the famous case of Dolly the sheep). This is a huge advancement for science, but it begs the question: is cloning ethical?

Cloning is, by definition, the creation of a genetically identical copy of an organism via asexual reproduction. Essentially, it’s like creating an unnatural identical twin: cloning duplicates a set of cells and produces a new being with the potential to live a separate and unique life. Despite both organisms sharing genetic makeup, it does not in any way define how the cloned person or organism would behave; it would only guarantee identical DNA between the original and the clone.

There are reasons for which cloning would be biologically beneficial. Consider the following scenario: a patient in a hospital is in desperate need of a heart transplant, but there are younger and more desirable patients above them on the waiting list for a transplant. If the cloning process were applied to this circumstance, scientists could harvest a microscopic amount of DNA from the patient and, in time, construct an entirely new heart similar to their own, reducing the chances of rejection and giving more people a greater chance of survival. Lives could be saved and organ donation could become unnecessary. Phasing out organ donors through the normalization of medical cloning would protect the person’s posthumous body and calm the minds of their loved ones in a time of mourning.

Courtesy of the Chinese Academy of Sciences

Cloning plants could also benefit the environment. Assuming cloning is environmentally feasible and less expensive than the world’s mass production of agriculture, cloning high-demand plant crops, such as grain, would reduce agricultural water use and possibly decrease the cost of healthy foods. With the high amount of people living below the poverty line, access to cost-efficient nutritious foods is almost nonexistent, so many of them turn to cheap, processed options such as fast food and boxed meals. Under the assumption that cloning plants is successful, this could financially help impoverished people improve their health while living under a strict budget.

However, just because something can be cloned doesn’t mean that it should be. If this behavior is normalized, cloning for corporate purposes, such as cosmetic products being tested on animals, could become commonplace. The morality of testing human-used products on animals is constantly debated by politicians and

citizens alike, but environmentalists argue that it is unethical to subject an innocent, unknowing being to such cruelty, even if it’s “just a clone.” Clones have as much value as the original being and can still feel pain. Inflicting harm on cloned animals is just as immoral as testing on natural-born animals.

All things considered, cloning is like most aspects of modern technology in that it may be used for good and for bad, depending on who has access to it. Hopefully, if or when cloning hits the mainstream, there will be laws and regulations set in place to protect the dignity of all life.